By William Derham, Research & Collections

In recent weeks, a row of fencing has appeared in the south-west corner of the Lower Yard at Dublin Castle, announcing the beginning of what will be a two-year conservation project on one of the oldest parts of the Castle: the Medieval Tower. Thanks to the generous financial support of Fáilte Ireland, scaffolding will be erected soon and work will begin on reviving one of the oldest structures in the Castle. Over eight centuries, this tower has stood its ground when all around it was changing, adapting to these changes from within rather than without.

Photograph by Mark Reddy, Trinity Digital Studios

Photograph by Mark Reddy, Trinity Digital Studios

‘The old black tower to the westward of the chapel is to be demolished as a useless fabric that gives a disgraceful gloominess to the Viceregal residence, little according with the style and elegance of the other parts.’

So wrote The Dublin Evening Post on 3 September 1793. The useless fabric referred to was the oldest surviving part of the medieval Castle of Dublin, the construction of which had begun several centuries earlier following instructions issued by King John in 1204. In the king’s words, a castle was required to provide a ‘… safe place for the custody of our treasure … for the administration of justice and if need be for the defence of the city’.

The old black tower that was to be demolished in 1793 had been one of the four corner towers of that castle. A map of 1673 refers to it as the ‘Gunner’s Tower’, and it has been suggested that it may have been home of the Master Gunner of Ireland. A few years later, in 1678, Robert Ware described it as the ‘Wardrobe Tower’, adding that it provided access to the chapel that was next to it. In medieval and early-modern times, the Royal Wardrobe was a mix of storehouse and workshop, acquiring raw materials like fabric and furs and turning them into clothes and livery. Ware described it as ‘…a repository for the royal robe … and other furniture of state’.

Reproduced courtesy of Philip Maddock

Reproduced courtesy of Philip Maddock

A large fire in 1684 resulted in the destruction of a large part of Dublin Castle, and after the fire many of the surviving medieval buildings were demolished to make way for newer, more comfortable buildings of red brick with large windows and slated roofs. Many of these survive in the form of the Georgian Castle we see today.

However, whether through lack of resources or apathy, or a combination of both, the ‘old black tower’ survived the rebuilding. At this stage, it was known as the Wardrobe Tower, but it was still providing access to the Castle Chapel and was also being used as a prison. In 1689, during the Williamite Wars, Archbishop William King was imprisoned in Dublin Castle. He kept a diary of his time there which suggests that the Wardrobe Tower was the place of his confinement. As late as 1804 parts of it were still being used for this purpose, and The Dublin Evening Post reported on the escape of a prisoner who climbed up a chimney flue onto the roof and then descended by the drainpipe onto the Castle terrace.

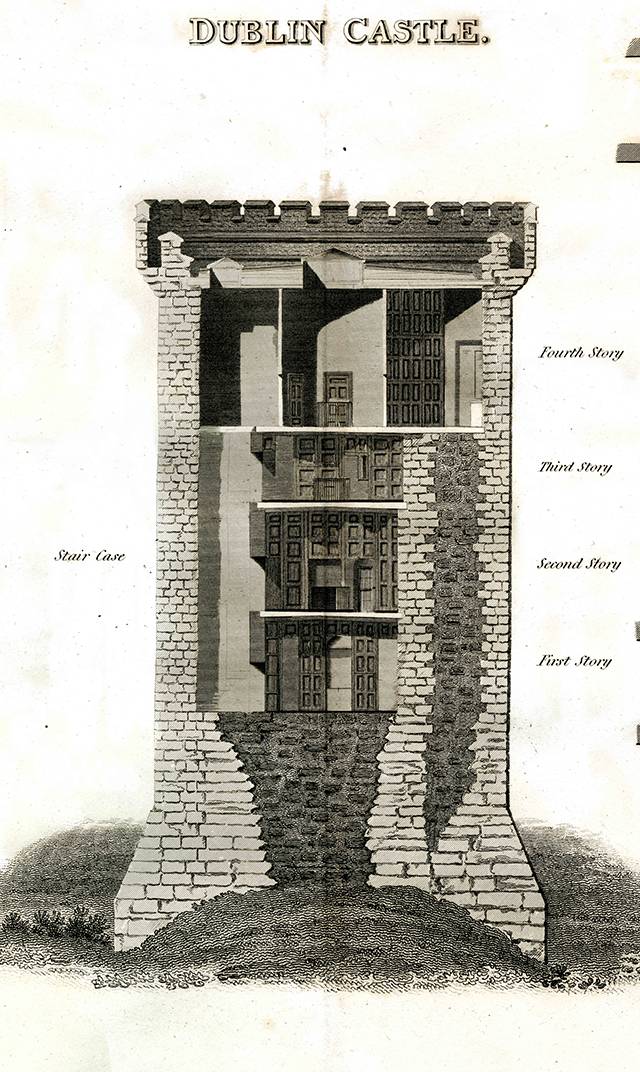

The survival of this ‘useless fabric’ left the way open for new possibilities. On 1 September 1810, the Irish Record Commission was established to assess the condition of the public records of Ireland and to make recommendations for their upkeep and preservation. A year later, on 3 September 1811, the Board of Works wrote to Francis Johnston, its architect, asking for ‘… a Plan and Estimate to be prepared with as much expedition as possible for fitting up the whole of the Tower … as a repository of Public Records, it being the intention of Government, to move the records named in the margin into the said Tower, as soon as it can be fitted up’. The list in the margin read: ‘The Parliamentary Records, State Paper Office, Surveyor Gen. of Lands, Office of Arms, Records now in the Bermingham Tower’. The cost of this ‘fitting up’ was estimated at ‘five thousand, five hundred and seventy one pounds, thirteen shillings and two pence’.

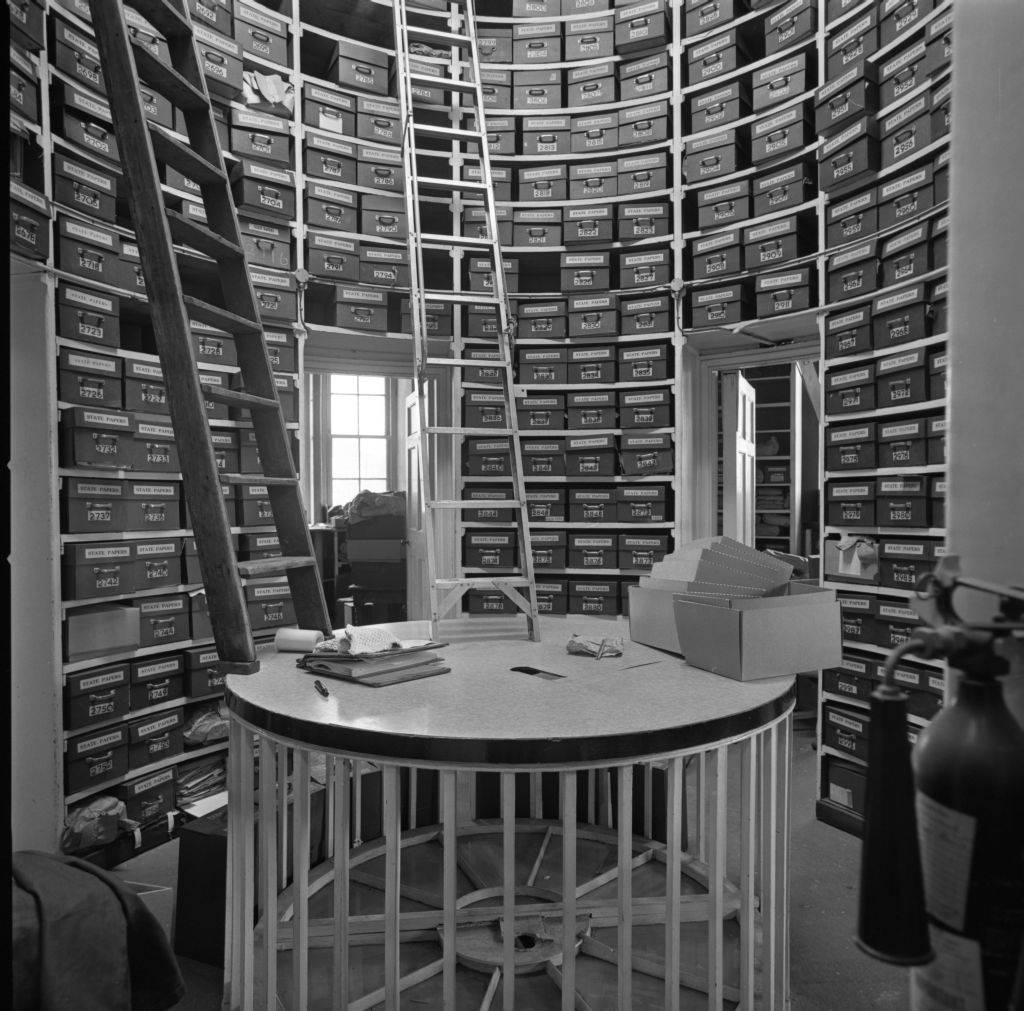

Francis Johnston was at that time working on replacing the old Castle Chapel, which adjoined the Tower, with his new Chapel Royal. He added another storey to the Tower, topped with battlements, which blended harmoniously with his new Gothic-revival Chapel. The spaces within the tower were lined with wooden presses for the storage of records and documents, while offices occupied the new storey added to the top of the structure. And so, the Wardrobe Tower became known as the Record Tower. In the 1860s, Johnston’s wooden presses were replaced with open pine shelving which held cartons of papers. This was done on the advice of Sir John Bernard Burke, Keeper of the State Papers, who described the new system of storage as ‘the only protection in the world against our invincible enemy – DUST’.

Photograph by Seán O’Reilly, courtesy of the Irish Architectural Archive

Photograph by Seán O’Reilly, courtesy of the Irish Architectural Archive

The passing of the National Archives Act in 1986 heralded the end of the Tower’s use as a repository for records. Under its terms, all state papers were consolidated at the National Archives’ premises on Bishop Street, Dublin. On 16 August 1991, the National Archives formally left the Tower. Minimal work was done to the building and it next became home to the Museum of the Garda Síochána, the Irish police force, who opened their doors to the public on August 17, 1997. The Garda Síochána recently left the Tower for a new home on the other side of the Lower Castle Yard.

Last year, an exciting partnership was announced between Fáilte Ireland and the Office of Public Works to conserve the Tower with a view to opening it to the public in 2019. Its survival as one of the oldest, most intact, and most important parts of the city of Dublin is impressive. Its history of changing inhabitants and roles shows it to have been much more useful than The Dublin Evening Post suggested in 1793. Throughout its 800-year history, its massive walls have been used at different times to keep people out and to keep people in; at other times, to protect valuable treasures from accident or theft. All the time it bore silent witness to the vagaries of Irish history as they unfolded in and around Dublin Castle. It is that history that we hope to start sharing with visitors in an exciting new museum space in the Medieval Tower from 2019 onwards.