By Dr James Curry, Guide & Information Officer

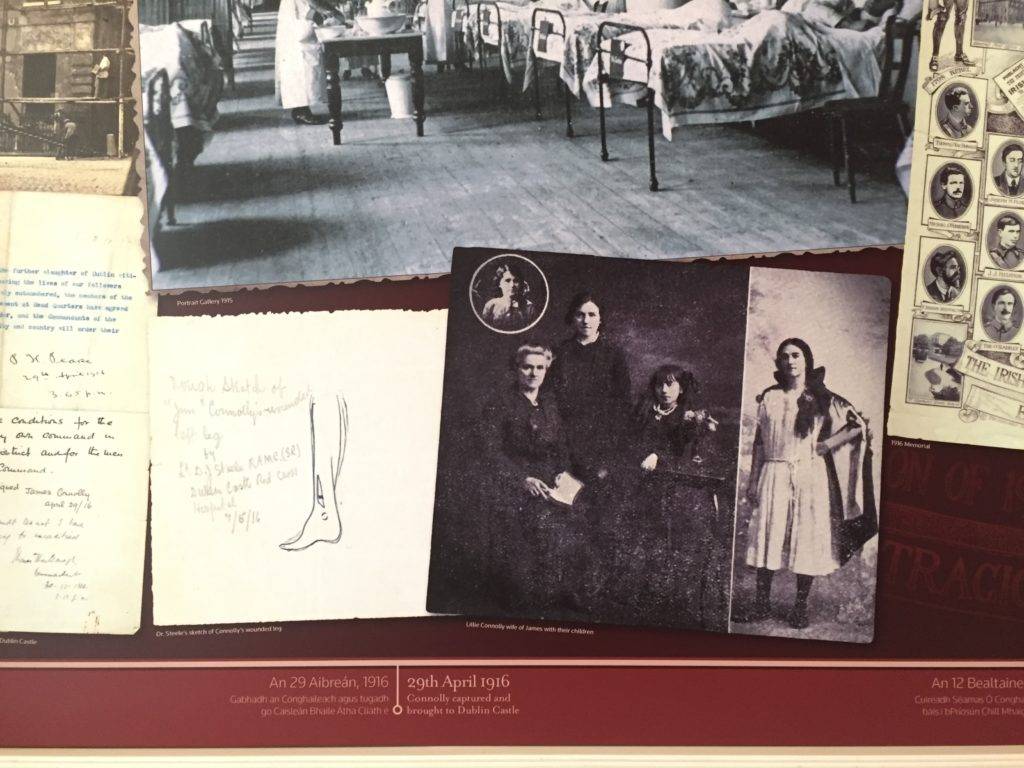

Photograph of Lillie Connolly with four of her daughters featured on a display in the James Connolly Room at Dublin Castle’s State Apartments, which was formerly part of the 2016 In the Shadow of the Castle: Dublin Castle in 1916 exhibition. The photograph first appeared in a 1917 Dublin booklet published by the Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependents’ Fund (Photograph by James Curry).

In a chapter dealing with the aftermath of James Connolly’s execution in his 2005 biography of the great revolutionary and labour leader, historian Donal Nevin concluded with the following remarks:

When Lillie Connolly called to General Maxwell to collect her executed husband’s belongings, he advanced to meet her and held out his hand. She looked him straight in the eyes and held her hands behind her. Permission for the Connolly family to go to America was later refused.

No source was cited for this information, likely supplied in some form by James and Lillie’s daughter Nora, with the reader left assuming that General John G. Maxwell, who ordered the Easter Rising executions, subsequently reacted to the handshake snub by denying Lillie and her children the opportunity to fulfil Connolly’s wishes and emigrate to the United States during the summer of 1916.

James and Lillie Connolly’s grandson James Connolly (fourth from left), son of Roddy Connolly (1901-1980), with some of his children and other descendants at the special ‘James Connolly and the State Apartments’ tour given at Dublin Castle on 12 May 2018 (Photograph by Seán Connolly).

Maxwell actually acted very differently, at least initially, as revealed by the contents of a declassified ‘Dublin Castle’ intelligence file held at the U.K. National Archives in Kew. This Colonial Office file shows that shortly after ignoring Maxwell’s offer of a handshake en route to claiming some of her executed husband’s belongings from Major Ivor Price, Lillie Connolly called to the Metropolitan Police Office at Dublin Castle to apply for passport permits for herself and her five daughters. ‘According to the wishes of his late father’, the 15-year-old Roderick – who had served in the GPO during the opening days of the Easter Rising as an Irish Citizen Army scout and messenger, for which he was briefly imprisoned – was to temporarily remain in Dublin to complete his education at Blackrock College.

A senior DMP figure named O’Mahony, when commenting on Lillie Connolly’s passport application with Sir Edward O’Farrell, the Assistant Under Secretary for Ireland, was sympathetic towards ‘the poor woman [who] is naturally very much upset and in a highly nervous condition’. This emotional state of mind perhaps explains why she misunderstood the Metropolitan Police Office clerk’s instructions over how to go about applying for the necessary travel permits. Although O’Mahony’s superior, Superintendent Owen Brien of the DMP’s Detective Division, was of the opinion on 8 June that ‘in the present condition of affairs it may not be desirable to issue these passports’, four days later General Maxwell made a notable attempt to influence the Under Secretary for Ireland, Sir Robert Chalmers, with the following note:

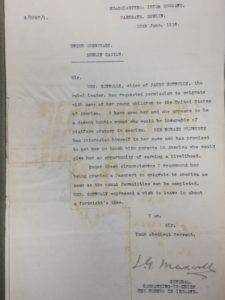

Mrs. Connolly, widow of James Connolly, the rebel leader, has requested permission to emigrate with some of her young children to the United States of America. I have seen her and she appears to be a decent humble woman who would be incapable of platform oratory in America. Sir Horace Plunkett has interested himself in her case and has promised to get her in touch with persons in America who would give her an opportunity of earning a livelihood. Under these circumstances I recommend her being granted a Passport to emigrate to America as soon as the usual formalities can be completed. Mrs. Connolly expressed a wish to leave in about a fortnight’s time.

General John G. Maxwell’s letter to Sir Robert Chalmers, the Under Secretary for Ireland, on 12 June 1916, recommending that Lillie Connolly, ‘a decent humble woman’, be granted the necessary passport permits to emigrate to the United States with her children (U.K. National Archives).

It would prove to be Maxwell’s sole effort to ensure that the grieving family was allowed to emigrate, for in the interim Robert Dunlop of the RIC had responded to a request for information as to whether Lillie Connolly could ‘safely be certified as a fit and proper person’ to travel to America or if ‘she or any of her daughters [were] likely to start an anti-British campaign if permitted to proceed’, by sending a negative report to the DMP from Belfast on 10 June. Although he was willing to raise the possibility that ‘perhaps they could do less harm in the States than if they were left in Ireland’, Dunlop reported that ‘Mrs Connolly and her family have always taken an active part in the extreme movements’ while living in Belfast, and he was in no doubt that their actions and associates during this period indicated that ‘they will lend their aid to anything that goes to injure Gt. Britain’ if permitted to return to America.

The news left the DMP’s Chief Commissioner of the opinion that the family should be denied passports since ‘they would be very likely to start an anti-British campaign in the States and would in all probability be exploited by James Larkin’ (who had departed for America in October 1914). Yet, as ever, responsibility over the matter was to rest with the British government, leaving the DMP to take the precaution on 14 June of suggesting to Chalmers that were she to be allowed travel, Lillie Connolly be searched after she and her family had boarded the liner for the United States, in case she had been ‘entrusted with important documents by the Rebels’.

This proposed search would not prove necessary, for two days later Chalmers had no problem receiving the approval of Home Secretary Herbert Samuel in refusing to sanction the granting of passports. For General Maxwell’s information, an explanation was sent to Major Price. This was redundant, with Price revealing on 18 June that the military commander did ‘not now wish to press for Mrs. Connolly to be allowed to go to U.S.A. … as it has been ascertained that George Russell (“A.E.”) who recommended her being allowed to go appears to be a close friend of James Larkin’.

Dreading the thought of returning to ‘such a mixed political atmosphere as that of Belfast’, after eventually abandoning her plan to emigrate to America, Lillie Connolly chose to make the short journey from family friend William O’Brien’s home in Mountjoy Square, where she had been staying since after the Easter Rising, and set up home in Drumcondra. She would stay based in Dublin for the remainder of her life, initially with her only son and daughters Aideen, Ina, Moira and Fiona. In time she was also joined by her eldest surviving daughter. For as will be discussed at a later date, in September 1916 Dublin Castle became aware that ‘Nora Connolly, daughter of James Connolly, executed rebel’ had ignored the decision of authorities and defiantly stowed away to the United States …

James Connolly monument in Chicago’s Union Park, erected by the Irish-American Labor Council of Chicago in October 2008 (Photograph by James Curry).