By Muireann Walsh, Guide & Information Officer

This year Poetry Day Ireland is inviting us to share, read and celebrate poetry at home and online. Here at Dublin Castle we have decided to put our own twist on the theme ‘There will be time’. Seeing as Poetry Day Ireland coincides with the 104th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, we have chosen to look to the past and remember the poetry that anticipated or was inspired by this pivotal event in Irish history.

Don’t forget to share your experience and photos using the hashtag #PoetryDayIRL

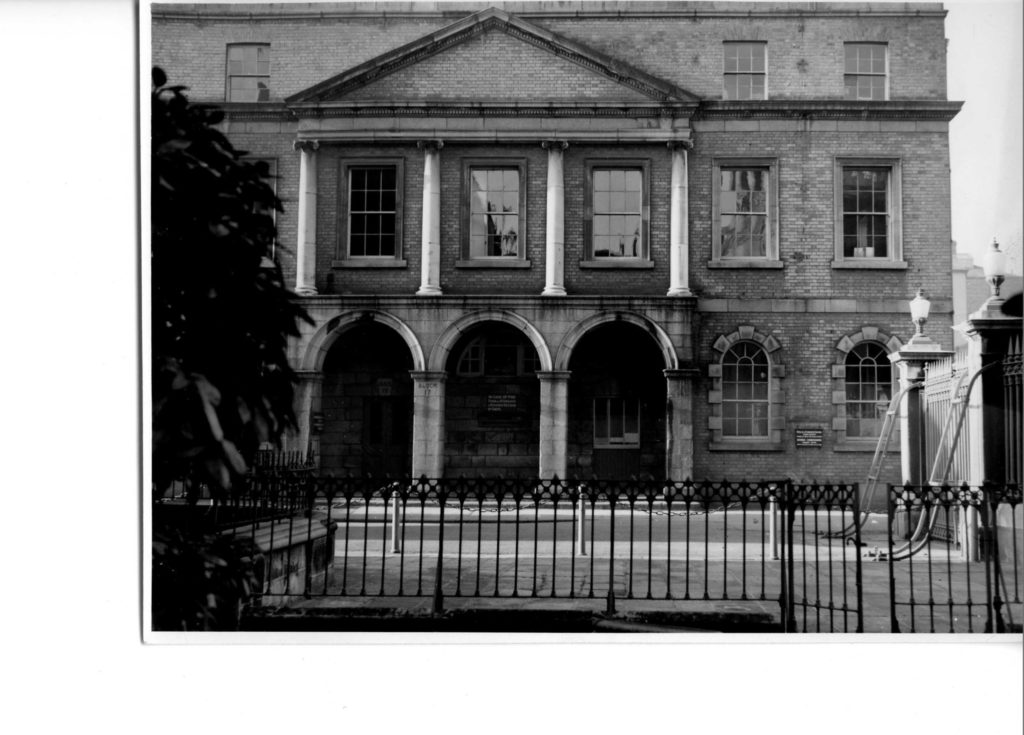

Cork Hill Gate. From ‘Buildings and places in the Dublin Castle area, associated with the Rising of Easter Week 1916’. Courtesy of the Bureau of Military History.

Poetry of the 1916 leaders

The revolutionary spirit and fervent belief in Irish independence characterises the poetry of three of the Irish Proclamation’s signatories: Patrick Pearse, Joseph Plunkett and Thomas MacDonagh.

#1 Patrick Pearse: The Rebel

I am come of the seed of the people, the people that sorrow,

That have no treasure but hope,

No riches laid up but a memory

Of an Ancient glory.

My mother bore me in bondage, in bondage my mother was born,

I am of the blood of serfs;

The children with whom I have played, the men and women with whom I have eaten,

Have had masters over them, have been under the lash of masters,

And, though gentle, have served churls;

The hands that have touched mine, the dear hands whose touch is familiar to me,

Have worn shameful manacles, have been bitten at the wrist by manacles,

Have grown hard with the manacles and the task-work of strangers,

I am flesh of the flesh of these lowly, I am bone of their bone,

I that have never submitted;

I that have a soul greater than the souls of my people’s masters,

I that have vision and prophecy and the gift of fiery speech,

I that have spoken with God on the top of His holy hill.

And because I am of the people, I understand the people,

I am sorrowful with their sorrow, I am hungry with their desire:

My heart has been heavy with the grief of mothers,

My eyes have been wet with the tears of children,

I have yearned with old wistful men,

And laughed or cursed with young men;

Their shame is my shame, and I have reddened for it,

Reddened for that they have served, they who should be free,

Reddened for that they have gone in want, while others have been full,

Reddened for that they have walked in fear of lawyers and of their jailors

With their writs of summons and their handcuffs,

Men mean and cruel!

I could have borne stripes on my body rather than this shame of my people.

And now I speak, being full of vision;

I speak to my people, and I speak in my people’s name to the masters of my people.

I say to my people that they are holy, that they are august, despite their chains,

That they are greater than those that hold them, and stronger and purer,

That they have but need of courage, and to call on the name of their God,

God the unforgetting, the dear God that loves the peoples

For whom He died naked, suffering shame.

And I say to my people’s masters: Beware,

Beware of the thing that is coming, beware of the risen people,

Who shall take what ye would not give.

Did ye think to conquer the people,

Or that Law is stronger than life and than men’s desire to be free?

We will try it out with you, ye that have harried and held,

Ye that have bullied and bribed, tyrants, hypocrites, liars!

#2 Patrick Pearse: The Mother

I do not grudge them: Lord, I do not grudge

My two strong sons that I have seen go out

To break their strength and die, they and a few,

In bloody protest for a glorious thing,

They shall be spoken of among their people,

The generations shall remember them,

And call them blessed;

But I will speak their names to my own heart

In the long nights;

The little names that were familiar once

Round my dead hearth.

Lord, thou art hard on mothers:

We suffer in their coming and their going;

And tho’ I grudge them not, I weary, weary

Of the long sorrow – And yet I have my joy:

My sons were faithful, and they fought.

#3 Patrick Pearse: Mise Éire

| Mise Éire: Sine mé ná an Chailleach BhéarraMór mo ghlóir: Mé a rug Cú Chulainn cróga.Mór mo náir: Mo chlann féin a dhíol a máthair.Mór mo phian: Bithnaimhde do mo shíorchiapadh.Mór mo bhrón: D’éag an dream inar chuireas dóchas.Mise Éire: Uaigní mé ná an Chailleach Bhéarra. |

I am Ireland: I am older than the Hag of Beara.Great my glory: I who bore brave Cú Chulainn.Great my shame: My own children that sold their mother.Great my pain: My irreconcilable enemies who harass me continually.Great my sorrow: That crowd, in whom I placed my trust, decayed.I am Ireland: I am lonelier than the Hag of Beara. |

#4 Thomas MacDonagh: Wishes for my Son

Now, my son, is life for you,

And I wish you joy of it,-

Joy of power in all you do,

Deeper passion, better wit

Than I had who had enough,

Quicker life and length thereof,

More of every gift but love.

Love I have beyond all men,

Love that now you share with me-

What have I to wish you then

But that you be good and free,

And that God to you may give

Grace in stronger days to live?

For I wish you more than I

Ever knew of glorious deed,

Though no rapture passed me by

That an eager heart could heed,

Though I followed heights and sought

Things the sequel never brought.

Wild and perilous holy things

Flaming with a martyr’s blood,

And the joy that laughs and sings

Where a foe must be withstood,

Joy of headlong happy chance

Leading on the battle dance.

But I found no enemy,

No man in a world of wrong,

That Christ’s word of charity

Did not render clean and strong-

Who was I to judge my kind,

Blindest groper of the blind?

God to you may give the sight

And the clear, undoubting strength

Wars to knit for single right,

Freedom‘s war to knit at length,

And to win through wrath and strife,

To the sequel of my life.

But for you, so small and young,

Born on Saint Cecilia’s Day,

I in more harmonious song

Now for nearer joys should pray-

Simpler joys: the natural growth

Of your childhood and your youth,

Courage, innocence, and truth:

These for you, so small and young,

In your hand and heart and tongue.

#5 Joseph Mary Plunkett: I See His Blood Upon the Rose

I see his blood upon the rose

And in the stars the glory of his eyes,

His body gleams amid eternal snows,

His tears fall from the skies.

I see his face in every flower;

The thunder and the singing of the birds

Are but his voice—and carven by his power

Rocks are his written words.

All pathways by his feet are worn,

His strong heart stirs the ever-beating sea,

His crown of thorns is twined with every thorn,

His cross is every tree.

Following their surrender, Pearse and MacDonagh were the first of the rebels to be executed by firing squad on the 3rd May 1916, with Plunkett suffering the same fate the following day. Nevertheless, these men and their conviction will be forever immortalised in their poetry.

The Guardhouse. From ‘Buildings and places in the Dublin Castle area, associated with the Rising of Easter Week 1916’. Courtesy of the Bureau of Military History.

Contemporary Interpretations

The cultural impact of the 1916 Rising and its ideals can also be felt beyond the inner circle of the revolutionary leaders. Poetry composed by the likes of W. B. Yeats, George ‘AE’ Russell, Eva Gore-Booth, Francis Ledwidge, Joyce Kilmner and James Stephens reflect the contemporary viewpoints of the rebellion in Ireland and abroad. Themes of sacrifice, irrevocable change, grief and hope encapsulate their interpretations of events.

#6 W. B. Yeats: Easter 1916

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

That woman’s days were spent

In ignorant good-will,

Her nights in argument

Until her voice grew shrill.

What voice more sweet than hers

When, young and beautiful,

She rode to harriers?

This man had kept a school

And rode our wingèd horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road,

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashes within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute by minute they live:

The stone’s in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

That is Heaven’s part, our part

To murmur name upon name,

As a mother names her child

When sleep at last has come

On limbs that had run wild.

What is it but nightfall?

No, no, not night but death;

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

#7 W. B. Yeats: Sixteen Dead Men

O but we talked at large before

The sixteen men were shot,

But who can talk of give and take,

What should be and what not

While those dead men are loitering there

To stir the boiling pot?

You say that we should still the land

Till Germany’s overcome;

But who is there to argue that

Now Pearse is deaf and dumb?

And is their logic to outweigh

MacDonagh’s bony thumb?

How could you dream they’d listen

That have an ear alone

For those new comrades they have found,

Lord Edward and Wolfe Tone,

Or meddle with our give and take

That converse bone to bone?

#8 George ‘A. E.’ Russell: To the Memory of Some I Knew Who are Dead and Loved Ireland

Their dream had left me numb and cold,

But yet my spirit rose in pride,

Refashioning in burnished gold

The images of those who died,

Or were shut in the penal cell.

Here’s to you, Pearse, your dream not mine,

But yet the thought, for this you fell,

Has turned life’s water into wine.

You who have died on Eastern hills

Or fields of France as undismayed,

Who lit with interlinked wills

The long heroic barricade,

You, too, in all the dreams you had,

Thought of some thing for Ireland done.

Was it not so, Oh, shining lad,

What lured you, Alan Anderson?

I listened to high talk from you,

Thomas MacDonagh, and it seemed

The words were idle, but they grew

To nobleness by death redeemed.

Life cannot utter words more great

Than life may meet by sacrifice,

High words were equalled by high fate,

You paid the price. You paid the price.

You who have fought on fields afar,

That other Ireland did you wrong

Who said you shadowed Ireland’s star,

Nor gave you laurel wreath nor song.

You proved by death as true as they,

In mightier conflicts played your part,

Equal your sacrifice may weigh,

Dear Kettle, of the generous heart.

The hope lives on age after age,

Earth with its beauty might be won

For labor as a heritage,

For this has Ireland lost a son.

This hope unto a flame to fan

Men have put life by with a smile,

Here’s to you Connolly, my man,

Who cast the last torch on the pile.

You to, had Ireland in your care,

Who watched o’er pits of blood and mire,

From iron roots leap up in air

Wild forests, magical, of fire;

Yet while the Nuts of Death were shed

Your memory would ever stray

To your own isle. Oh, gallant dead-

This wreath, Will Redmond, on you day.

Here’s to you, men I never met,

Yet hope to meet behind the veil,

Thronged on some starry parapet,

That looks down upon Innisfail,

And sees the confluence of dreams

That clashed together in our night,

One river, born from many streams,

Roll in one blaze of blinding light.

#9 Eva Gore-Booth: Comrades

The peaceful night that round me flows,

Breaks through your iron prison doors,

Free through the world your spirit goes,

Forbidden hands are clasping yours.

The wind is our confederate.

The night has left her doors ajar,

We meet beyond earth’s barred gate.

Where all the world’s wild Rebels are.

#10 Francis Ledwidge: Lament for Thomas MacDonagh

He shall not hear the bittern cry

In the wild sky, where he is lain,

Nor voices of the sweeter birds,

Above the wailing of the rain.

Nor shall he know when loud March blows

Thro’ slanting snows her fanfare shrill,

Blowing to flame the golden cup

Of many an upset daffodil.

But when the Dark Cow leaves the moor

And pastures poor with greedy weeds

Perhaps he’ll hear her low at morn

Lifting her horn in pleasant meads.

#11 Francis Ledwidge: Lament for the Poets: 1916

I heard the Poor Old Woman say:

“At break of day the fowler came,

And took my blackbirds from their songs

Who loved me well thro’ shame and blame.

“No more from lovely distances

Their songs shall bless me, mile by mile,

Nor to white Ashbourne call me down

To wear my crown another while.

“With bended flowers the angels mark

For the skylark the place they lie;

From there its little family

Shall dip their wings first in the sky.

“And when the first surprise of flight

Sweet songs excite, from the far dawn

Shall there come blackbirds loud with love,

Sweet echoes of the singers gone.

“But in the lovely hush of eve,

Weeping I grieve the silent bills,”

I heard the Poor Old Woman say

In Derry of the little hills.

#12 Francis Ledwidge: O’Connell Street

Noble failure is not vain

But hath a victory of its own

A bright delectance from the slain

Is down the generations thrown.

And, more than Beauty understands

Has made her lovelier here, it seems;

I see white ships that crowd her strands,

For mine are all the dead men’s dreams.

#13 Joyce Kilmer: Easter Week

(In memory of Joseph Mary Plunkett)

(“Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone,

It’s with O’Leary in the grave.”)

—William Butler Yeats.

“Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone,

It’s with O’Leary in the grave.”

Then, Yeats, what gave that Easter dawn

A hue so radiantly brave?

There was a rain of blood that day,

Red rain in gay blue April weather.

It blessed the earth till it gave birth

To valour thick as blooms of heather.

Romantic Ireland never dies!

O’Leary lies in fertile ground,

And songs and spears throughout the years

Rise up where patriot graves are found.

Immortal patriots newly dead

And ye that bled in bygone years,

What banners rise before your eyes?

What is the tune that greets your ears?

The young Republic’s banners smile

For many a mile where troops convene.

O’Connell street is loudly sweet

With strains of Wearing of the Green.

The soil of Ireland throbs and glows

With life that knows the hour is here

To strike again like Irishmen

For that which Irishmen hold dear.

Lord Edward leaves his resting place

And Sarsfield’s face is glad and fierce.

See Emmet leap from troubled sleep

To grasp the hand of Padraic Pearse!

There is no rope can strangle song

And not for long death takes his toll.

No prison bars can dim the stars

Nor quicklime eat the living soul.

Romantic Ireland is not old.

For years untold her youth shall shine.

Her heart is fed on Heavenly bread,

The blood of martyrs is her wine.

#14 James Stephens: The Spring in Ireland, 1916

I

Do not forget my charge I beg of you ;

That of what flow’rs you find of fairest hue

And sweetest odor you do gather those

Are best of all the best — a fragrant rose,

A tall calm lily from the waterside,

A half-blown poppy leaning at the side

Its graceful head to dream among the corn,

Forget-me-nots that seem as though the morn

Had tumbled down and grew into the clay,

And hawthorn buds that swing along the way

Easing the hearts of those who pass them by

Until they find contentment. — Do not cry,

But gather buds, and with them greenery

Of slender branches taken from a tree

Well bannered by the spring that saw them fall:

Then you, for you are cleverest of all

Who have slim fingers and are pitiful,

Brimming your lap with bloom that you may cull,

Will sit apart, and weave for every head

A garland of the flow’rs you gathered.

II

Be green upon their graves, O happy Spring,

For they were young and eager who are dead;

Of all things that are young and quivering

With eager life be they remembered :

They move not here, they have gone to the clay,

They cannot die again for liberty;

Be they remembered of their land for aye;

Green be their graves and green their memory.

Fragrance and beauty come in with the green,

The ragged bushes put on sweet attire,

The birds forget how chill these airs have been,

The clouds bloom out again and move in fire;

Blue is the dawn of day, calm is the lake,

And merry sounds are fitful in the morn;

In covert deep the young blackbirds awake,

They shake their wings and sing upon the morn.

At springtime of the year you came and swung

Green flags above the newly-greening earth;

Scarce were the leaves unfolded, they were young,

Nor had outgrown the wrinkles of their birth:

Comrades they thought you of their pleasant hour,

They had but glimpsed the sun when they saw you;

They heard your songs e’er birds had singing power,

And drank your blood e’er that they drank the dew.

Then you went down, and then, and as in pain,

The Spring affrighted fled her leafy ways,

The clouds came to the earth in gusty rain,

And no sun shone again for many days:

And day by day they told that one was dead,

And day by day the season mourned for you,

Until that count of woe was finished,

And Spring remembered all was yet to do.

She came with mirth of wind and eager leaf,

With scampering feet and reaching out of wings,

She laughed among the boughs and banished grief,

And cared again for all her baby things;

Leading along the joy that has to be,

Bidding her timid buds think on the May,

And told that Summer comes with victory,

And told the hope that is all creatures’ stay.

Go, Winter, now unto your own abode,

Your time is done, and Spring is conqueror

Lift up with all your gear and take your road,

For she is here and brings the sun with her:

Now are we resurrected, now are we,

Who lay so long beneath an icy hand,

New-risen into life and liberty,

Because the Spring is come into our land.

III

In other lands they may,

With public joy or dole along the way,

With pomp and pageantry and loud lament

Of drums and trumpets, and with merriment

Of grateful hearts, lead into rest and sted

The nation’s dead.

If we had drums and trumpets, if we had

Aught of heroic pitch or accent glad

To honor you as bids tradition old,

With banners flung or draped in mournful fold,

And pacing cortege; these would we not bring

For your last journeying.

We have no drums or trumpets ; naught have we

But some green branches taken from a tree,

And flowers that grow at large in mead and vale;

Nothing of choice have we, or of avail

To do you honor as our honor deems,

And as your worth beseems.

Sleep, drums and trumpets, yet a little time;

All ends and all begins, and there is chime

At last where discord was, and joy at last

Where woe wept out her eyes: be not downcast,

Here is prosperity and goodly cheer,

For life does follow death, and death is here.

Ship Street Barracks. From ‘Buildings and places in the Dublin Castle area, associated with the Rising of Easter Week 1916’. Courtesy of the Bureau of Military History.

The Rising Legacy Today

The 1916 Rising continued to influence the medium of poetry throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. In 2016, the Republic of Ireland celebrated the centenary of the Easter Rising. As part of the commemoration, the Irish Writers Centre commissioned works from leading Irish poets including Eiléan Ní Chuillenáin, Paul Muldoon, Jessica Traynor, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill and Theo Dorgan. Their collection of poems expands upon previous interpretations by focusing on various figures and locations associated with the Rising.

#15 Liam MacGabhann: Connolly (1933)

The man was all shot through that came today

Into the barrack square;

A soldier I – I am not proud to say

We killed him there;

They brought him from the prison hospital;

To see him in that chair

I thought his smile would far more quickly call

A man to prayer.

Maybe we cannot understand this thing

That makes these rebels die;

And yet all things love freedom – and the Spring

Clear in the sky;

I think I would not do this deed again

For all that I hold by;

Gaze down my rifle at his breast – but then

A soldier I.

They say that he was kindly – different too,

Apart from all the rest;

A lover of the poor; and all shot through,

His wounds ill drest,

He came before us, faced us like a man,

He knew a deeper pain

Than blows or bullets – ere the world began;

Died he in vain?

Ready – present; And he just smiling – God!

I felt my rifle shake

His wounds were opened out and round that chair

Was one red lake;

I swear his lips said ‘Fire!’ when all was still

Before my rifle spat

That cursed lead – and I was picked to kill

A man like that!

#16 Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin: FOR JAMES CONNOLLY

i

When I think of all the false beginnings …

The man was a pair of hands,

the woman another pair,

to be had more cheaply,

the wind blew, the children were thirsty –

when he passed by the factory door he saw them,

they were moving and then waiting,

as many as the souls that crowded by Dante’s boat

that never settled in the water –

what weight to ballast that ferry?

They are there now, as many

as the souls blown by the winds of their desire,

the airs of love,

not one of them weighing

one ounce against the tornado

that lifts the lids of houses, that spies

where they crouch together inside

until the wind sucks them out.

It is only the wind, but what braced muscle, what earthed foot

can stand against it, what voice so loud

as to be heard shouting Enough?

ii

He had driven the horse in the rubbish cart, he knew

the strength in the neck under the swishing mane,

he knew how to tell her to turn, to back or stand

He knew where the wind hailed from, he studied

its language, it blew in spite of him.

He got tired waiting for the wind to change,

as we are exhausted waiting for that change,

for the voices to shout Enough , for the hands

that can swing the big lever and send the engine rolling

away to the place we saw through the gap in the bone

where there was a painted room, music and the young people

dancing on the shore, and the Old Man of the Sea

had been sunk in the wide calm sea.

iii

he sea moves under the wind and shows nothing

– not where to begin. But look for the moment

just before the wave of change crashes and

goes into reverse. Remember the daft beginnings

of a fatal century and their sad endings, but let’s not

hold back our hand from the lever. Remember James Connolly,

who put his hand to the work, who saw suddenly

how his life would end, and was content because

men and women would succeed him, and his testament

was there, he trusted them. It was not a bargain:

in 1916 the printer locked the forme,

he set it in print, the scribes can’t alter an iota

– then the reader comes, and it flowers again, like a painted room.

#17 Theo Dorgan: WE CARRIED IT TO HERE AS BEST WE COULD

‘Miss, did you hear that, Miss, what Commandant Connolly said?’

A boy, oblivious to the leg wound I am binding.

‘When we were coming down Abbey Street only yesterday,

William O’Brien said, where are we going Jim and, and

the Commandant’s answer, we are going to be slaughtered.

What do you think, Miss, is that the right of it, would you say?’

His eyes are away, caught by the crash of rifles, of glass

sparkling inward from the explosion — he would not hear me

if I answered, having just discovered that all of this

is actually happening, and to him, here and now.

The women bring tea in a bucket, brisk and efficient,

smokebothered, filthy and cheerful. Dead men piled to the side,

we try not to look at them, or to breathe when we go near;

the wounded we draw deeper inside, we do what we can

to ease their pain. Beside me, an old volunteer reloads

— perhaps with bullets I smuggled in. He stands, takes aim, fires —

a figure drops outside Clerys, spasms and flattens out.

The flames are struggling to take hold upstairs. The noise, the roar,

I had not expected the noise, the stink, the filth of it —

blood, cordite, the toilets blocked, black plaster dust everywhere.

Connolly beckoning to Pearse, their bare heads together.

A smouldering beam thuds down behind them, flames lick the air.

Break out. Through Moore Street. Send out the women under a flag.

Crowbar and pickaxe work, save what we can… We won’t save you,

I think. Keep my counsel. The long retreat inside ourselves

has begun. Thunder outside as another building falls,

the guns walking their hell steadily towards us. Fire is their

answer to our stubborn persistence; they could starve us out

if they wished, but some demon drives them, they want we should burn

for the sin of pride, rebels against their divine order

‘…to prevent further slaughter…’ The words are agreed, scrawled out

by lamplight. This morning we watched a father and his child,

waving a soiled bedsheet, gunned down as they ran from shelter.

‘They will not fire on a woman’ — I mean to remember

the man who said that, one of the few poor innocents left.

Gathered all that I had been until now, my time on earth,

stood, smoothed my skirts, pinned up my hair. Pearse, by the stretcher,

sought my eyes: ‘Now, Liz, be of good heart. This is not defeat,

we’ve made a good beginning now, we’ve carried it to here.’

I bowed my head, I would not weep. The walls, the roof, crashed in.

Dead bodies in doorways, on the streets, this I remember,

the stench, quick swarming flies… and not just soldiers — volunteers,

yes, but ordinary men and women, and children too,

my god, the children! I was too horrified to feel fear

but I walked on, a cold prickling like electricity

on my skin, walked under the guns, seeing madness in some eyes.

I felt strange to myself, pushed out onto a nightmare stage,

but rage steadied me when some aide threatened to shoot me.

His superior grim, unbending, severe in his terms.

I drew on my own cold reserves, I made him give his word.

I caught the flash of sunlight on lens, saw the camera raised —

and time slowed. I made quick calculation: the General f

acing Pearse crisp and commanding, our own man upright but

wearied by cares, flanked by a nurse, saw what would come of this,

to what purpose it could be put… I stepped to one side, stood

out of the record —for the dignity of our cause, yes,

and for a second reason, one that came suddenly clear:

I knew we would fight on, would rise from this burning carnage,

I saw no reason the enemy should have my image:

I held myself out of their history, to make my own.

#18 Jessica Traynor: A DEMONSTRATION

Letter by this morning’s post to say I may go home for Xmas

if I won’t have a demonstration (do they picture bands?)

– Dr Kathleen Lynn

What might drive me, a doctor,

to jump out of reason and into the fire

of rebellion? Haunted by skulls

that boast through the thin skin of children

who ghost the alleyways, dying

young in silent demonstration,

I raise my own demonstration

against my limits as woman and doctor.

I remember those I’ve watched dying

of gulping coughs, praise the mercy of gunfire

that scythes through women and children.

I number those dead, count their skulls.

Outside city hall, a policeman’s skull, s

hattered by a bullet. This is less a demonstration,

more a bewilderment of poets and children,

watched over by one errant doctor.

My convictions temper in the fire

and quicklime of what follows, the dying

man brought out and shot at dawn, the everdying

Cuchulainn with his necklace of skulls –

all that spitting, revolutionary fire.

And my part in that demonstration

won’t be forgotten, but as a woman doctor

put down to hysteria, or a lack of children –

for what are women really but children

themselves, living and dying

without reason? They say a real doctor

might cure me, could measure my skull

and tell its emptiness, demonstrate

my zeal was nothing but a mindless fire.

A rebel dying stokes the nation’s fire,

but starving children? Ask this doctor

to number our gains in skulls. Expect a demonstration.

#19 Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill: ÍOTA AN BHÁIS

Can amach ainm an Raithilligh.

B’fhíor gach ní adúirt Yeats;

Munar thaoiseach é ó thús ó dhúchas,

Do bhaist sé é féin le fuil.

Ba gheall é leis an Samhildánach

Ag teacht go doras an dúna.

An raibh bua ar bith de bhuanna an domhain

Nach raibh aige in aonacht?

Má bhí ceol uathu, ba cheoltóir é

Do sheinn an pianó is do chanadh.

Má ba ealaíon, ba ealaíontóir,

Do línigh sé armas is craobha ginealaigh.

Bhí sé ina fheidhmeannach, ina iriseoir.

Bhí Fraincís ar a thoil aige.

Do thiomnaigh sé a bhuanna go léir

Do Cháit Ní Dhuibhir, don chúis náisiúnta.

Chaith sé deireadh seachtaine iomlán na Cásca

Ag taisteal bóithre na Mumhan

Ag cur ordú cealaithe Mhic Néill i bhfeidhm

Ó Chiarraí go Tiobraid Árainn

Mar sin féin, nuair a tháinig an Luan

Is gur thuig sé go raibh an cath coiteann,

Do thiomáin sé go hArdOifig an Phoist.

Ina ghluaisteán De Dion-Bouton.

Má fhiafraíonn éinne cad í an chúis

Leis an athrú, tá’s againn a chuid focal;

‘Nó gur chabhraíos chun an clog a thochras

Tá sé chomh maith agam é a chlos ag bualadh’.

Ach má tá rud ar bith go bhfuil a chlú

Is a cháil ag brath air, tá sé mar thoradh

Ar an bhfogha a tugadh síos Sráid Uí Mhórdha

Is é féin i gceannas an ruathair.

Bhí daoine níos ciallmhaire ná é,

A thuig gur ruathar é in aisce,

Go raibh meaisínghunna ag arm Shasana

A dhéanfadh ciota fogha dos na fearaibh.

Ach do sheas sé sa bhearna baoil.

Ni hamháin gur sheas ach do shiúil ann.

Thuig gur gníomh buile ab ea an t-Éirí Amach

Ach má b’ea, ba bhuile ghlórmhar.

An lá a chuas ar thuras siúlóide

Ag leanúint lorg an Rathailligh

Bhí léirsiú ar siúl ar fuaid an bhaill

Agus agóid i Sráid an Mhórdhaigh.

Is é a dúirt muintir na sráide

Is iad ag caint go líofa ón ardán

Gur deineadh faillí ar an áit d’aonghnó

Is gurb é an Stát a bhí ciontach san éagóir.

‘Céad biain ó shoin, le linn an Éirí Amach

Do throideamair in aghaidh na Sasanach.

Anois táimid i gcoinne ár muintire féin.’

An náire dhamanta, an íoróin.

Mar do chuimhníos láithreach ar an bhfear

A luafar go deo mar ghaiscíoch.

A ruathar mire fan na sráide céanna

Is claíomh ina láimh aige á bheartú.

Nuair a thángas go dtí an leac comórtha

Mar a bhfuil fáil ar a scríbhinn dheireanach,

Ní fhéadfainn na focail a dhéanamh amach

Tré bheith geamhchaoch ó ghol agus le déistin.

Ag cuimhneamh ar an bhfear a scrígh

Ag fáil bháis go mall is go hanacrach.

Naoi nuair an chloig déag ag céiliúr

Gan gearán ná éagaoin, is fós gan cabhair.

Is sa deireadh nuair a rug íota an bháis

Ar a scórnach is gur lorg sé uisce

Níor scaoileadar chuige oiread is deor

Le teann díoltais agus mioscaise.

Mar sin can amach ainm an Rathailligh

Can amach go deo a ghlóir.

An taon duine de cheannairí na Cásca

A cailleadh ar pháirc an Áir.

#20 Paul Muldoon; PATRICK PEARSE: A MANIFESTO

It’s good to see a number of St Enda’s boys

willing to volunteer, displaying something like defiance

when we’ve too often been content to deploy

ourselves in Turkey, to philander

as sappers and sepoys

on the battlefields of France.

His ankle shattered, Connolly

has commandeered

two girls from Cumann na mBan to dance

attendance on him. No less ungainly,

I look askance

at a young man whose mouth is smeared

with fresh strawberries.

His lifeblood itself sapped

while British soldiers jeered.

Another’s arm is as obstreperous,

having just veered

off the stretcher to which he’s strapped

as if to mock the verities.

One by one they’ve heard their names

called and snapped

to attention, Ferdia after Ferdia

falling rapt

before Cuchulainn at a ford. The frame

of a butcher’s bicycle

is listing so badly one of its legs is surely as game

as Connolly’s. It’s all but Paschal,

this orange-black flame

that hastens still through the GPO.

Even if the British artillery

have been inclined to greet

my earlier manifestos

with a salvo of their own, The O’Rahilly

is determined to show

that if we don’t share the sweet

taste of victory,

at least for now we may find joy

in our retreat to the Williams and Woods jam factory

in Parnell Street.