By William Derham, Collections, Research & Interpretation

It can be hard to gain a good picture of Dublin Castle sometimes. Metaphorically speaking, it looms large in the story of Ireland’s struggle for independence and yet relatively little has been written about the building itself, or the events that actually took place there. This is particularly true of the revolutionary period, from 1919 to 1922.

From a physical point of view, this is understandable. Even today, the Castle is little noticed as one walks the streets of Dublin around it. Glimpses are gained at places like Palace Street, Cork Hill and Ship Street, but none of these offers a penetrating view that would help to clarify in the mind of a passer-by the form, quantity, variety or layout of the buildings within. Perhaps this physical ‘distance’ has resulted in ‘Dublin Castle’ being seen more as a by-word for the colonial administration that occupied it, rather than as a reference to the actual buildings themselves.

One location where the bricks and mortar of the Castle meet with specific events of history, however, is passed by many Dubliners each day, without much notice ever been taken of it. Most are probably unaware that the dark brown-brick front of what looks like a typical Georgian house facing onto Exchange Court, next to City Hall, was at one point the base of “F” Company of the ADRIC – the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary, better known to Irish history simply as “the Auxiliaries”.

Exchange Court, Dublin.

The Auxiliaries were formed in July 1920. They were made up largely of former army officers, and were intended to be a nimble, mobile paramilitary force. They were deployed to support the work of the Royal Irish Constabulary and quickly earned a reputation for brutality, largely due to their carrying out of indiscriminate reprisals amongst the Irish population in revenge for attacks by the IRA (Irish Republican Army).

One of the many acts for which the Auxiliaries were responsible occurred one hundred years ago this week. The 21st November, 1920 is remembered in Irish history as “Bloody Sunday”. On that morning, Michael Collins’s “Squad” shot fourteen suspected British military and intelligence officers at locations across the city of Dublin. Later that day, at a Gaelic football game between Dublin and Tipperary in Croke Park stadium, British forces fired indiscriminately into the crowd of spectators, killing a further fourteen people. Each of these episodes is well known, and has been subject to much discussion and argument. However, that night, the slaughter of the day was book-ended with a third atrocity, the death of three men in police custody at Dublin Castle.

The night before Bloody Sunday, 20th November, Peadar Clancy and Dick McKee had been captured by the Auxiliaries in a premises on Gloucester Street (now Sean McDermott Street) in Dublin’s north inner-city. Both men had fought in the 1916 Easter Rising and were heavily involved in the IRA and its war against Britain – Clancy was vice-commandant of the Dublin Brigade and Dick McKee was its OC, or commanding officer. Both had also been involved in the planning of the assassinations of suspected British intelligence officers that took place the following morning.

Also arrested that same evening was Conor Clune. Clune had been involved in the Gaelic League, an organisation that promoted the Irish language, and worked as a clerk on the Raheen Co-op of Edward MacLysaght in Co. Clare. He had travelled to Dublin at the last minute with MacLysaght, the two of them arriving in the capital early on the evening of the 20th. As MacLysaght describes it in his memoir, Clune:

… went to see a man called John O’Connell at Vaughan’s hotel after leaving me on Saturday evening. His business was a matter connected with the Gaelic League, but it so happened that Michael Collins and other leading members of the Volunteers, who frequently used Vaughan’s Hotel as a rendezvous, were there at the time. The house was surrounded and they escaped by their usual channel but Conor, not being one of them, found himself alone when the Auxiliaries burst in and he was arrested. … it was mere chance which put him with them [Clancy & McKee] in the guard room in the Castle, where prisoners were lodged after being brought in.

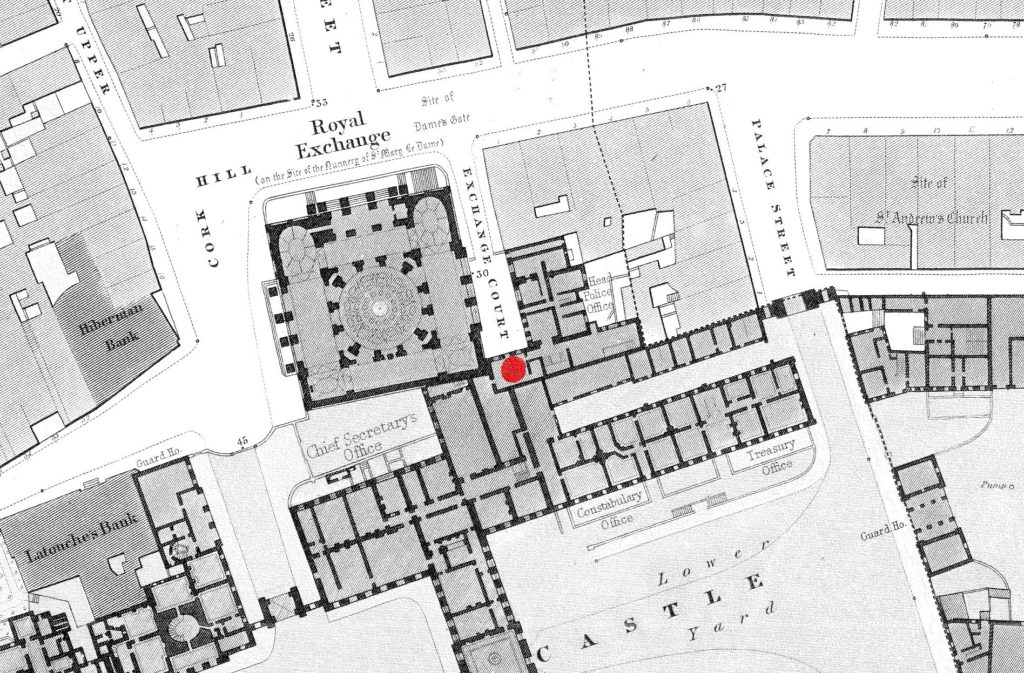

The three men, Clune, Clancy and McKee, were taken to the guard room of the Auxiliaries’s “F Company, which was located on the ground floor of the building at the southern end of Exchange Court. This old house, and two more adjoining it, had been taken over and used by different branches of the constabulary forces since the 1830s. It was interconnected with the range of buildings known as the Treasury Block that forms the northern side of the Lower Castle Yard (it is no longer part of Dublin Castle as we know it today).

Ordnance Survey Map, 1847 (detail) – the Guard Room is shown with a red dot.

What happened to the three men that night is still contested to this day, but none made it out of the guard room alive. Evidence suggests that they were possibly tortured and then killed in revenge for the day’s earlier killings. The government’s official line was that they were shot while trying to escape. So concerned were they to convey this version of events, that the scene was restaged for newspapers, illustrating exactly what the Auxiliaries said had happened (viewable in the Daily Graphic here, three quarters of the way down the page).

These three deaths soured what would otherwise have been considered to have been a great military and strategic success for the IRA. Liam Tobin remarked that they “knocked all the good out of it” and that the IRA “had no sense of jubilation as the enemy had evened up on us”.

Following an explosion in 1939, which damaged the carved, royal coat of arms above the central window of old Auxiliary guard room on Exchange Court, it was decided to replace it with a plaque to the memories of those who had died there on the eve of Bloody Sunday in 1920. The plaque is still there today. It reads, in Irish first, then English:

WITHIN THESE WALLS

BRIGADIER DICK MCKEE,

VICE BRIGADIER PEADAR CLANCY

AND VOLUNTEER CONOR CLUNE

I.R.A.

GAVE THEIR LIVES FOR THE

CAUSE OF IRISH INDEPENDENCE

ON SUNDAY, 21ST NOVEMBER, 1920.

The Memorial Plaque erected in 1939.

Bloody Sunday is one of the most notorious days associated with the Irish War of Independence. The last chapter of the events that unfolded that day is sometimes overlooked. One hundred years on, we remind people of the memorial that faces into Exchange Court, and of the lives that were lost that day at Dublin Castle.