Countess de Markievicz’s Despatch Bag

![]() Audio-description of Countess Markievicz’s Despatch Bag.

Audio-description of Countess Markievicz’s Despatch Bag.

Commentary by the curator Sinéad McCoole.

Commentary by curator Sinéad McCoole interpreted in Irish Sign Language

I had no idea that she belonged to “the Castle lot”.

By Evelyn Suttle, Guide & Information Officer

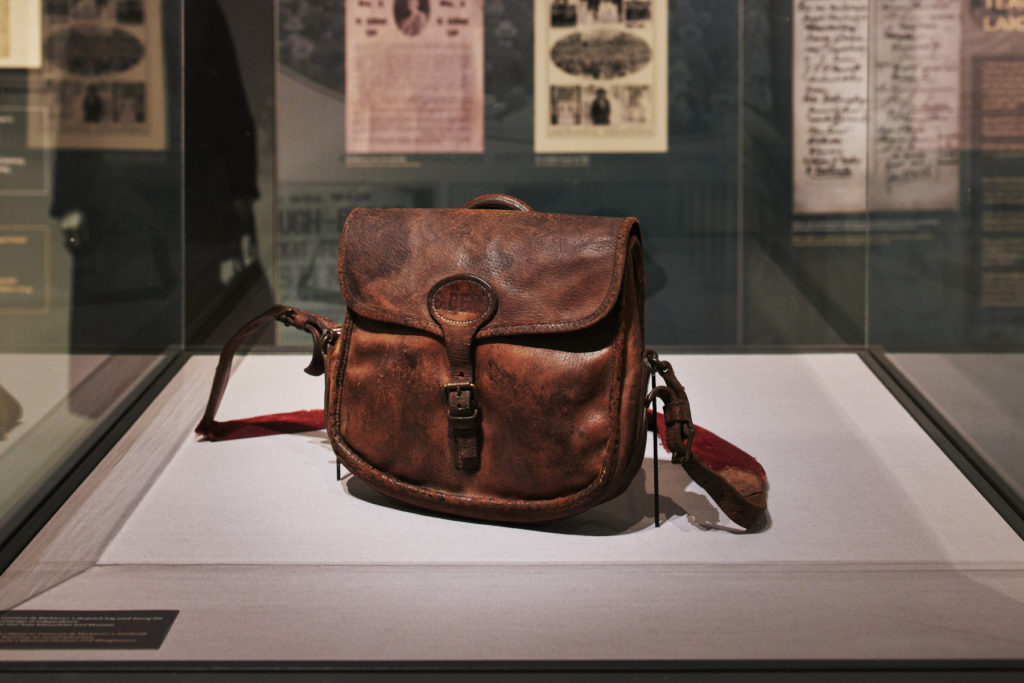

This despatch bag belonged to Countess de Markievicz (1868-1927), and is said to have been used during the 1916 Easter Rising and the campaign of independence. This Irish activist, revolutionary and politician from County Sligo was part of an armed rebellion, political campaigns and wars. If this bag could speak, undoubtedly it would have many astounding stories to tell. Whether discretely concealing a weapon or flaunting a green gown at a social event, Markievicz’s accessory choices often reflected her passion for revolution. A look back at her life may shed some light on the hardships and triumphs she saw.

“Dress suitably in short skirts and strong boots, leave your jewels and gold wands in the bank, and buy a revolver.”

~ Markievicz, C. (1915)1

Countess de Markievicz’s despatch bag used during the campaign of independence. On loan from Kilmainham Gaol Museum. Mála cáipéisí na Cuntaoise de Markievicz a úsáideadh i rith fheachtas an neamhspleáchais. Ar iasacht ó Mhúsaem Phríosún Chill Mhaighneann. Photo by Ros Kavanagh.

Countess de Markievicz (born Constance Gore Booth) grew up in Lissadell House, County Sligo, in the 19th century. She was brought to London to come out to society and find a suitable husband. Instead she enrolled in the Slade School of Art to study painting. She continued her studies in Paris, where she met Casimir Dunin-Markievicz. After the two married, she would go by his name ‘Markievicz’ from then on. ‘C. DE MARKIEVICZ’ is stamped underneath the handle on this bag and you can even see the initials ‘C. DE. M’ stamped above the buckle on the front.

In 1903 the couple settled in Dublin. Constance continued to paint while also performing in theatre. Lady Gregory once wrote of her: “I knew her in her Castle days when she was rather a jealous meddler in the Abbey… There was something gallant about her. We were each working for what we believed would help Ireland” (Gregory, 1947).2 For a while she juggled mingling with the aristocracy with growing political activism. She spoke in favour of the Sinn Féin cause for Irish Nationalism in 1908 and attended a meeting organised for a new nationalist-feminist journal. Helena Moloney remembered her arrival:

“She was already a staunch Feminist, and she eagerly accepted our invitation to attend a Committee meeting dealing with the forthcoming publication of “Bean na hEireann”. She came down one evening in an elaborate court gown, having come direct from some Castle function, which she left early in order to attend “this important Committee meeting”. None of us knew her personally, and I had no idea that she belonged to “the Castle lot”, or I might not have so light-heartedly sent her an invitation.”

~ Moloney, H (1934)3

By 1914 Constance was separated from her husband and had become increasingly active in political affairs and volunteer work. This had included providing aid, food and coal for families suffering during the 1913 Dublin lock-out.

The brown leather bag with a red fabric strap photographed here is believed to have been used in 1916. Constance was a commissioned officer in the Irish Citizen Army and helped plan for rebellion. She led a group to take over St Stephen’s Green Park and the College of Surgeons where she supposedly used this bag during the Easter Rising. After six days they surrendered and she was imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol.

She had been sentenced to death and was ready to die with her comrades but this sentence was then commuted to life imprisonment to avoid the scandal of a woman being executed. By many accounts, Markievicz was not relieved by this decision. She was transferred to Aylesbury Gaol in England. There she received visits from her sister Eva Gore Booth and Eva’s partner Esther Roper, who would try to cheer her up by arriving in brightly coloured borrowed outfits. You may not see Markievicz’s flair for colour on this bag, but the check pattern fabric on the inside and the red fabric strap may be a hint to this. Constance wrote to Eva following one of these visits:

“Always visit criminals in your best clothes, blue and grey for choice, if it’s me!… did you remember about the blue serge dress? P. Has the trunk. The key, a small one, was in a red leather bag left in Liberty Hall.”

~ Markievicz, C. (1916)4

In 1917, following a general amnesty, Markievicz was released. Rather than seek out a peaceful life, Markievicz decided to run for election the following year. She became the first woman elected to Westminster Parliament but she refused to take her seat in England. Instead she became the first woman to serve in Dáil Éireann, prior to Irish independence. While held in Mountjoy Prison during the War of Independence in 1920, Markievicz wrote:

“The police have finally given me back my clothes and toilet things, and all the contents of the bag are safe. I suppose someone is busy trying to concoct a charge against me. It takes a long time. I was wondering if anything would be planted in my bag!”

~ Markievicz, C. (1920)5

She was found guilty of promoting the youth organisation Fianna Éireann, which “advocated the unlawful carrying of firearms and the inciting of His Majesty’s subjects to become disaffected” (Murphy, 2014, History of Na Fianna Éireann). For her involvement with the youth group she was sentenced to two years hard labour. She remarked “amusing to see that for starting the Boy Scouts in England, Baden Powell was made a Baronet! I bet he did not work as hard as I did!” (Markievicz, 1921, pg. 266).6

When the Irish Free State was established in 1922, with a parliament swearing allegiance to the crown, Markievicz was not happy with this agreement falling short of a fully independent Irish Republic. She sided with Eamon De Valera’s national movement and was a founding member of Fianna Fáil in 1926.

This year may have seemed the start of a political career reborn, but it also brought the tragic news of the death of Constance’s sister Eva. This devastated Markievicz who had always confided in Eva and felt a spiritual connection to her, even when trapped in a prison cell. She kept in contact with Eva’s partner Esther but still felt that no one could understand her pain. One of the last letters written by Markievicz reads:

“I feel very sad leaving this house, probably for the last time. Every corner in it speaks of Eva, and her lovely spirit of peace and love is here just the same as ever. And Esther… I feel so glad Eva and she were together and so thankful that her Love was with Eva to the end.”

~ Markievicz, C. (1926)7

A year later, Constance de Markievicz was found to have peritonitis and died in 1927. This bag was later donated to the Kilmainham Jail Restoration Society by David Andrews, whose mother Mary Coyle was a friend of Constance de Markievicz. This Irish revolutionary left behind a legacy which can still be remembered today through her writings, her paintings, her items and the changes she made to the country she loved.

Endnotes and References

- Ward, M (1995), Women and Irish Nationalism, p. 46 The University of Michigan: Attic Press

- Gregory, I.A.P (1916-1930), Robinson, L (1947), Lady Gregory’s Journals, p. 238 The University of Michigan: Macmillan

- Moloney, H (1934), Witness Statement p. 10-11 Dublin, Bureau of Military History 1913-21

- Markievicz, C (1934), Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz, p. 152 London: Longman 81 Co

- Markievicz, C (1934), Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz, p. 253 London: Longman 81 Co

- Markievicz, C (1934), Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz, p. 266 London: Longman 81 Co

- Markievicz, C (1934), Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz, p. 315 London: Longman 81 Co

References:

Mackie, V. and Crozier-De Rosa, S. (2018) Remembering Women’s Activism London: Routledge

Ward, M (1995) In Their Own Voice: Women and Irish Nationalism the University of Michigan: Attic Press

Tiernan, S. (2013) Eva Gore-Booth: An image of such politics Manchester University Press

Special thanks to Kilmainham Gaol Museum and Lissadell House for providing further information.

Kathleen Clarke’s Chain

Chain of the President of the Court of Conscience, worn by Kathleen Clarke when she was Lord Mayor of Dublin. Slabhra Uachtarán na Cúirte Coinsiasa á chaitheamh ag Kathleen Clarke nuair ba í Ard-Mhéara Bhaile Átha Cliath.

Kathleen Clarke (née Daly) was the first female Lord Mayor of Dublin 1939-1941. It wasn’t just her sex that stood her apart from her predecessors but even refusal to caring on unquestioned traditions such as wearing the Lord Mayor’s Chain which came from King William of Orange. Instead she wore this chain of the President of the Court of Conscience.

Kathleen was born into the Daly family, a prosperous Fenian family from Limerick City, in 1878. Her uncle John Daly shared a cell with another Irish revolutionary named Thomas Clarke. Upon his release, Kathleen and Thomas Clarke began a correspondence and later a relationship. They moved to New York and were married before returned to Dublin in 1908 with three children.

Kathleen became a founding member of Cumann na mBan, an Irish Republican women’s organistion in 1914. Although both her brother Edward and her husband Thomas Clarke were executed following the 1916 Easter Rising, she provided support for other families involved by setting up the Irish National Aid Fund. She was imprisoned in Holloway Women’s Prison 1918-1919 but she didn’t stop there.

Over the next twenty years Kathleen Clarke would have an active political career. She went on to become a judge in the Republic Courts. She was a TD and a senator during the 1920s and became a founding member of Fianna Fáil. However, in 1937 she disagreed with Eamon de Valera’s new Constitution and its anti-woman attitudes. In 1939 she began two terms as Lord Mayor of Dublin. She retired on the grounds of ill-health. She remained active on various boards and committees. She spent the last seven years of her life living in Liverpool with her son Emmet and her two grandchildren. She died in 1972, aged 94.

Sources: Life in 1916 Ireland: Stories from statistics | Kathleen Clarke

Dublin City Council | The Women Behind the Men | Kathleen Clarke

Women’s Museum of Ireland | Kathleen Clarke

Bridget Redmond’s Mirror

A silver mirror presented to Bridget Redmond, 1933. On loan from her nephew John Mallick.

Scáthán airgid a bronnadh ar Bridget Redmond, 1933. Ar Iasacht óna nia, John Mallick.

This silver mirror was presented to Bridget Mary Redmond by the Nationalist Women of Waterford the first year she was elected to the Dáil in 1933. This would be the start of a long political career. She successfully contested 7 General Elections and continuously held her seat for her Waterford constituency until in 1952 she died while in office.

Although she was first elected as a member of Cumann na nGaedheal, this party amalgamated with the Centre Party and the Blue Shirts to become Fine Gael. She would be elected as a Fine Gael member for the next six elections.

In 1952 Bridget Mary Redmond died from pulmonary tuberculosis at the age of 47. She is buried at Newbridge Cemetery in County Kildare.

Sources: Houses of Oireachtas | Bridget Mary Redmond