By Dr James Curry, Guide & Information Officer

The James Connolly Room at Dublin Castle’s State Apartments, March 2018 (Photograph by James Curry)

Dedicated as it is to the life and death of one of the leaders of the Easter Rising, the James Connolly Room at Dublin Castle’s State Apartments often catches visitors by surprise. It was this room where the Edinburgh-born Commander of the Irish Citizen Army is believed to have been taken as a wounded prisoner prior to his execution at Kilmainham Gaol on 12 May 1916. Stationed at the General Post Office on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) during Easter Week, Connolly had been injured twice while outside the rebel headquarters. The first bullet wound to his left arm was relatively minor, but the later shrapnel injury to his left ankle proved far more serious and saw him bed-ridden before the rebels’ evacuation of the building on 28 April.

After the unconditional surrender of the following day, Connolly was taken on a stretcher from Moore Street to Dublin Castle, where parts of the State Apartments had been converted into a Red Cross Military Hospital to treat soldiers wounded in the First World War (read more about this in our earlier blog post, here). Months later, a volunteer nurse on duty at the time described the ‘unusual stir’ caused by Connolly’s arrival:

From the window I could see him lying on a stretcher, his hands crossed, his head hidden from view by the archway. The stretcher was on the ground, and at either side stood three of his officers, dressed in National Volunteer uniform; a guard of about thirty soldiers stood around. The scene did not change for ten minutes or more; somebody gruesomely suggested they were discussing whether he should be brought in, or if it would be better to shoot him at once. It is more likely they were arranging where he should be brought, and a small ward in the Officers’ Quarters, where he would be carefully guarded, was decided upon.

Much has been written by historians about Connolly’s final days, although it remains necessary to flesh out the narrative concerning his exact personal possessions upon arriving at Dublin Castle. A declassified Colonial Office file at the U.K. National Archives reveals that on 27 May, the Home Office sent the following memo to the Dublin Metropolitan Police:

Can you ascertain whether any money was found on James Connolly when arrested? It is presumed any property so found is now in possession of military authorities. The information is required for the assistant under secretary. Do you know if any formal arrangement has been made in regard to property found on prisoners?

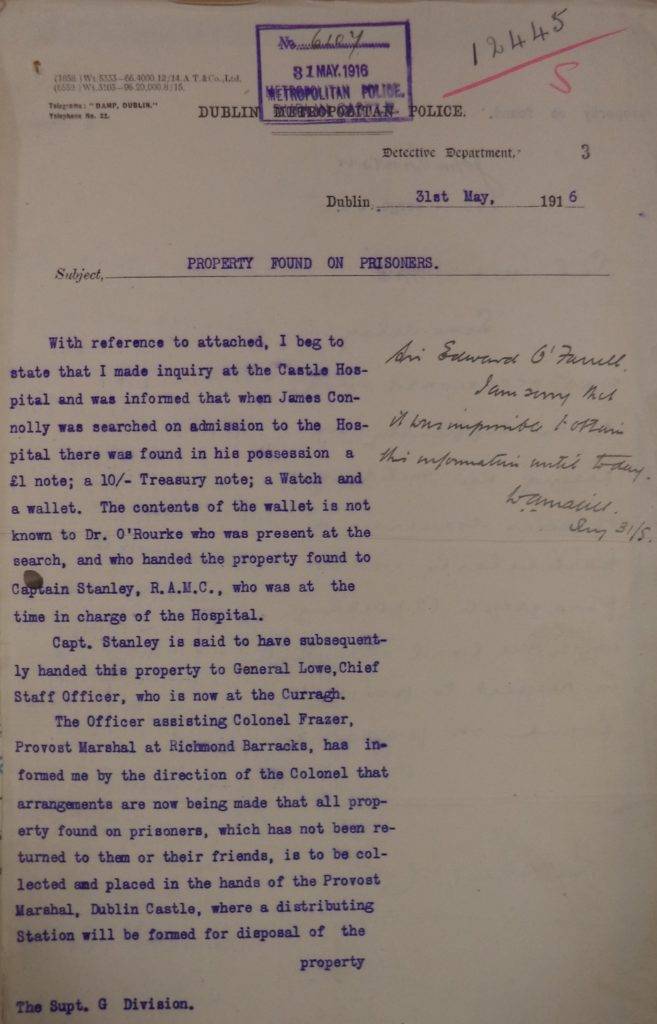

A page from the Colonial Office file regarding Connolly’s exact possessions upon his arrival at Dublin Castle’s State Apartments on Saturday, 29 April 1916 (U.K. National Archives)

After a delay of four days caused by ‘the difficulty in seeing the military officers concerned’, Sergeant John Bruton of the DMP’s ‘G’ (detective) Division was able to reveal that:

With reference to attached, I beg to state that I made inquiry at the Castle Hospital and was informed that when James Connolly was searched on admission to the Hospital there was found in his possession a £1 note; a 10/- Treasury note; a watch and a wallet. The contents of his wallet is not known to Dr. O’Rourke who was present at the search, and who handed the property found to Captain Stanley, R.A.M.C., who was at the time in charge of the Hospital. Capt. Stanley is said to have subsequently handed the property to General Lowe, Chief Staff Officer, who is now at the Curragh.

The Officer assisting Colonel Fraser, Provost Marshal at Richmond Barracks, has informed me by the direction of the Colonel that arrangements are now being made that all property found on prisoners, which has not been returned to them or their friends, is to be collected and placed in the hands of the Provost Marshal, Dublin Castle, where a distributing Station will be formed for disposal of the property so found.

It was the efforts of Connolly’s widow to recover his possessions that had led to the above correspondence taking place. On 7 June, John Maxwell, the General Officer Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in Ireland, was able to send the following note from ‘Headquarters, Irish Command, Parkgate, Dublin’:

Madame,

I understand that you have been enquiring for personal effects of your late husband. If you will kindly either call personally or send some trusted person to Major Price, this Office, he has been instructed to deliver a watch and money to whoever calls with proper authority from you. Perhaps it would be well to show this letter.

As regards your going to America, I am corresponding with Sir Horace Plunkett on this subject and hope to be able to give you permission to do so on hearing from him.

When Lillie Connolly (née Reynolds) opted to personally call on General Maxwell to collect her deceased husband’s belongings, she pointedly refused his offer of a handshake. An assumption that this snub may have contributed to the decision of authorities to prevent Lillie and her children from fulfilling Connolly’s wish that they return to the United States following his execution – referenced at the end of Maxwell’s note – is unfounded. Although this, like other matters connected with Connolly and his family from the period, is a story for another day …

Éamonn O’Doherty’s 1996 monument to James Connolly at Dublin’s Beresford Place (Photograph by James Curry)