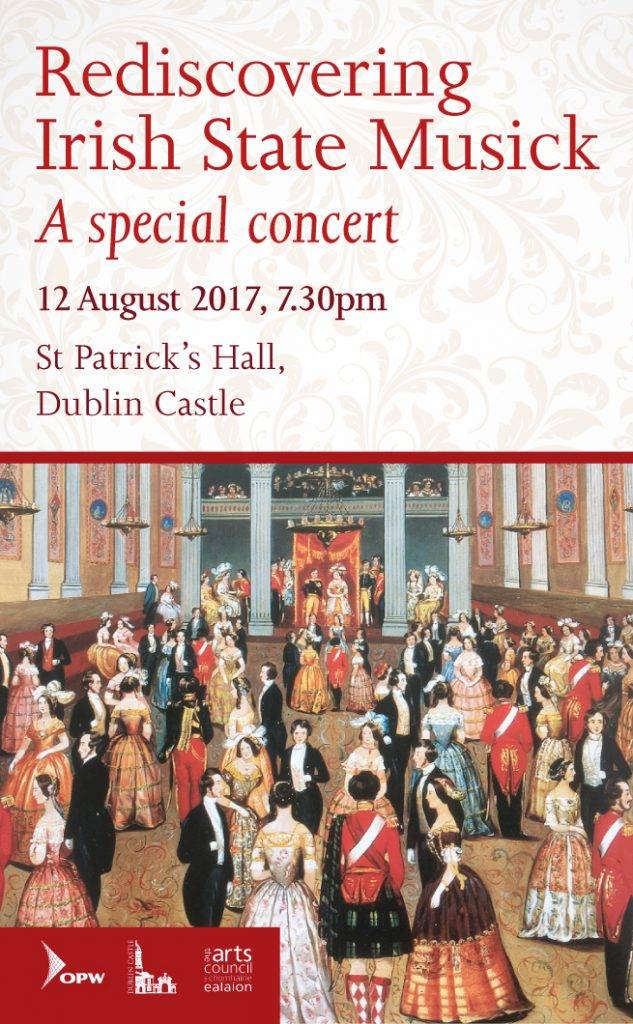

Peter Whelan, the founder and artistic director of Ensemble Marsyas, has a particular passion for exploring and championing neglected and forgotten music of the baroque era. On 12 August, you will be able to enjoy a rare treat in the splendid surrounding of St Patrick’s Hall when Peter will conduct compositions by Handel, Purcell, Vivaldi and other masters which were performed by – and in some cases written for – Irish State Musick, the band of virtuoso musicians based at Dublin Castle in the eighteenth century. Some of these pieces have only recently been rediscovered and have not been played in centuries, as Peter reveals in this guest post for our blog. Don’t miss out, make sure to book your ticket here!

Photograph courtesy of Jen Owens

Photograph courtesy of Jen Owens

This year, 2017, marks a double anniversary: the 275th anniversary of Messiah in Ireland and the 350th of the birth of Jonathan Swift. Swift might not have appreciated that coincidence. ‘I would not give a farthing for all the music in the universe’, he once remarked. But his acerbic commentary on the latest in musical fashions has inspired us to explore the broader social context of the musical performance in Ireland under the Georges and to seek answers to questions that have intrigued me since I was a child and learned the now-familiar fact that Messiah received its first performance in Fishamble Street, Dublin, in 1742. What did Handel find when he arrived in Ireland? Who were the Irish singers and musicians who so pleased Handel? What music gave soul to the elegant symmetries of Ireland’s Georgian architecture? What was the soundtrack to eighteenth-century Ireland?

It has been an enormous personal privilege for me to have this opportunity to work with such outstanding colleagues in stagecraft, performance and scholarship in developing this concert which will, I hope, introduce — or, rather, re-introduce — our audience to ‘new’ eighteenth-century Irish music while at the same time enabling us to experience familiar music with new ears.

This has only been possible because of the richness of musicological research in recent years by scholars who have unearthed documents of Irish musical interest in libraries and collections across the world. Perhaps the remarkable case of serendipitous survival is the Serenata by Johann Cousser, which we perform in our first concert: the score was returned to Germany in 1991 having been seized as war booty by the Red Army during the Second World War.

Thanks to remarkable discoveries such as these, we now have a much fuller picture of the music scene in Georgian Dublin. In particular, we understand a great deal about the size and make-up of the ‘Irish State Musick’ — the band based at Dublin Castle which would have been the primary provider of musicians for Handel. Now, we hope to breathe new life into the forgotten voices of the musicians of Ireland’s ‘Golden Age’, hearing them speak again for the first time in almost 300 years – eavesdropping on the leading composers and musicians whom Handel would have encountered working in Ireland in the eighteenth century.

Photograph courtesy of Jen Owens

Photograph courtesy of Jen Owens

One of the highlights is the Anthem by William Boyce (commissioned by the Mercer’s Hospital Charity) which has been completely overshadowed by Messiah. This exceptionally fine piece has a striking orchestral overture which was later reworked into a Symphony by Boyce.

Also the Serenata by Cousser, which is one of the earliest extant examples of opera composed in Ireland for Irish audiences complete with stage instructions (albeit on a small scale). Cousser here introduces the fashionable French style of Louis XIV’s Versailles to the Dublin Court. Look out for an early example of the pantomime dame – the character of Discord is clearly written for a tenor voice but is referred to as ‘she’ in the libretto.

Finally, the Dubourg, which is a particularly exciting discovery. Until now Matthew Dubourg was known primarily as a virtuoso violinist and for his association with Handel (mostly through the ‘Welcome Home, Mr. Dubourg!’ anecdote). All the works you will hear at the concert on 12 August have been salvaged from four volumes of manuscripts housed at the Royal College of Music in London which have almost certainly not been heard since their first performance in Dublin Castle in the eighteenth century (even the composer’s grandson did not know of their whereabouts). In this collection we also found some Irish traditional melodies sketched in Dubourg’s hand with lyrics phonetically translated from Gaelic into English (Dubourg was allegedly fond of attending country fairs and disguising himself as a fiddler).

The Odes show Dubourg to be an accomplished and charming composer and give us a tantalising indication of the qualities of the State Musick band. The composer’s close association with Handel is apparent in his style (perhaps we can even sense Handel leaning over his shoulder?) but there is enough galant-style individually to set Dubourg apart from his friend. Particularly touching is his tongue-in-cheek reference to his fellow State musicians in the aria, ‘But oh! What Skill what master Hand, Shall govern or constrain the wanton Band?’

With only a couple of weeks left before the concert, it is all go behind the scenes, but I cannot wait to share this music with you all and to finally reunite this music with its original location, adding an extra sensory dimension to our understanding of Dublin Castle.

Visit http://www.rediscoveringirishstatemusick.com/ for more information about Peter Whelan and the concert’s programme.